Picture Books

The children’s picture book industry originated and flourished in Victorian-era England, due in large part to the industrialization of printing processes and a changing society attitude about children. In Susan Meyer’s book, A Treasury of The Great Children’s Book Illustrators, she posits that “childhood is a middle-class invention of the nineteenth century“ (Strange how a century can claim the discovery of childhood). It had long been understood that children learned more quickly when words and pictures were combined. So, most children’s books were educational, but a new notion emerged that childhood was meant to be happy. Victorian-era England did not necessarily discover something new so much as set a standard of behavior toward children’s learning that we still follow today. In Joseph Schwarcz’s book, The Picture Book Comes of Age he states this idea simply by saying, “children have a right, as have adults to be amused.”

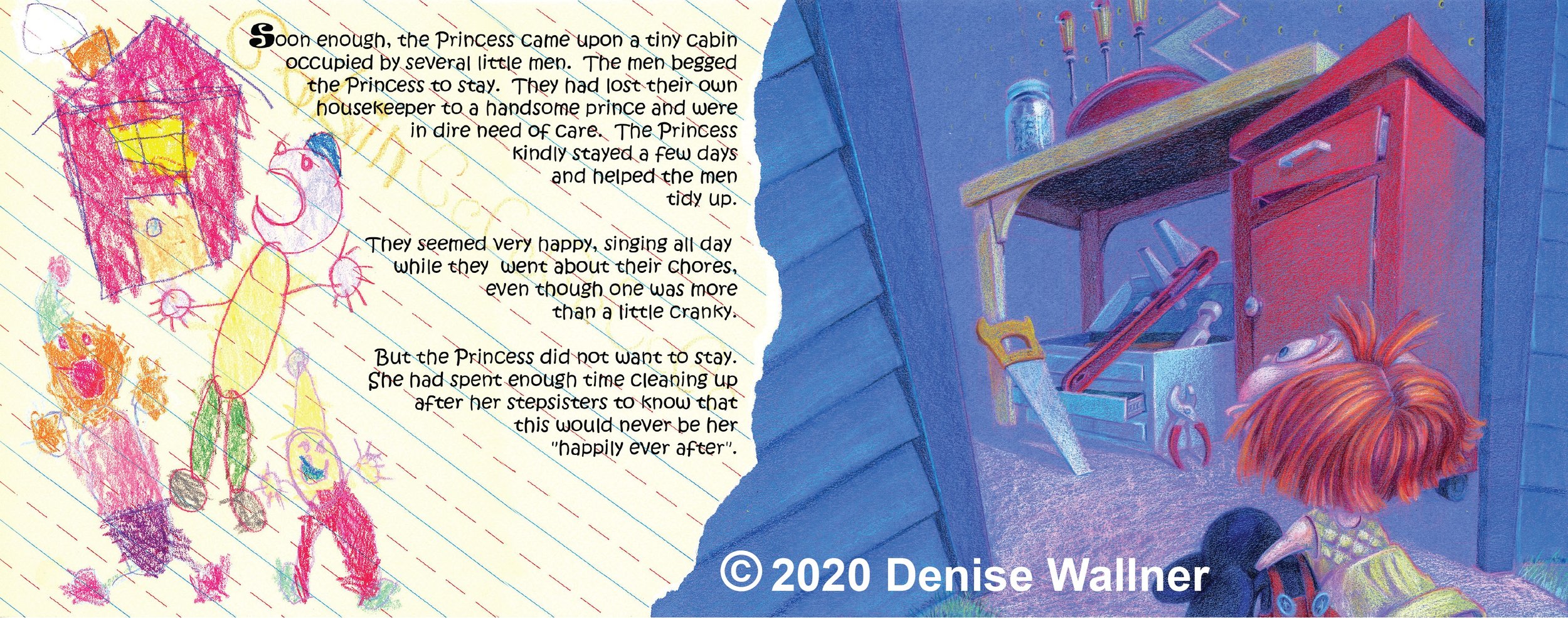

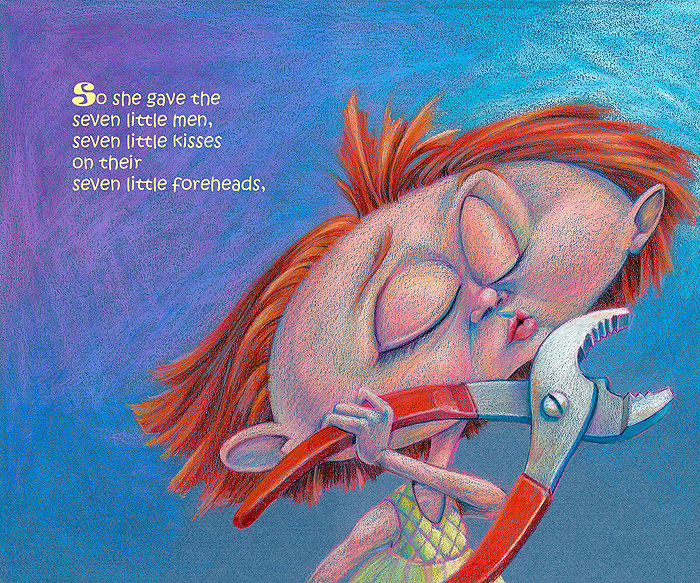

I definitely subscribe to that same notion that children must be amused by their books in order to engage their future interest in artwork and storytelling. That engagement will also assist them in understanding the world they will soon be encountering and how to navigate life’s complexities. In my first children’s book, Ever After (yes, I’m aware I must change the title), I challenge the idea of traditional fairy tales, particularly those that involve happily ever after endings that involve patriarchal gender norms. But I engage the reader and the child to view it through the point of view of a little girl at play who is narrating her own story as she recalls some traditional fairy tales.

In reimagining the folk tale, Teeny Tiny, I create a visual playfulness of relative ideas of size. In reimagining the folk tale, Teeny Tiny, I create a visual playfulness of relative ideas of size. Having only the manuscript to work from I was able to image a different ending and characters in the form of bunny slippers and furniture.

Exploring my illustrated voice, I revisited a multitude of skillsets and media. The tall tales of the Baron Munchausen reimagined needed remarkable soaring landscapes as well as intimate settings that vibed well with watercolors. The character looks remarkably like my mom in drag—not sure what that’s all about. A visual interpretation of Agoraphobia and Munch’s Scream-inspired face created the twisted world and dark shadows in my award-winning illustration of the same name. While bodily contortions of Lisa Yuskavage’s painting inspired the awkward interpretation of my Hey Diddle Diddle oil painting. I have an entire library of books that I look forward to diving into so I can bring the visuals in my head out into the world.

I’m considering making a series of Giselle prints of my work. If you’d be interested contact me via this website and let me know which piece you’d be interested in purchasing.

Milwaukee Sketchbook

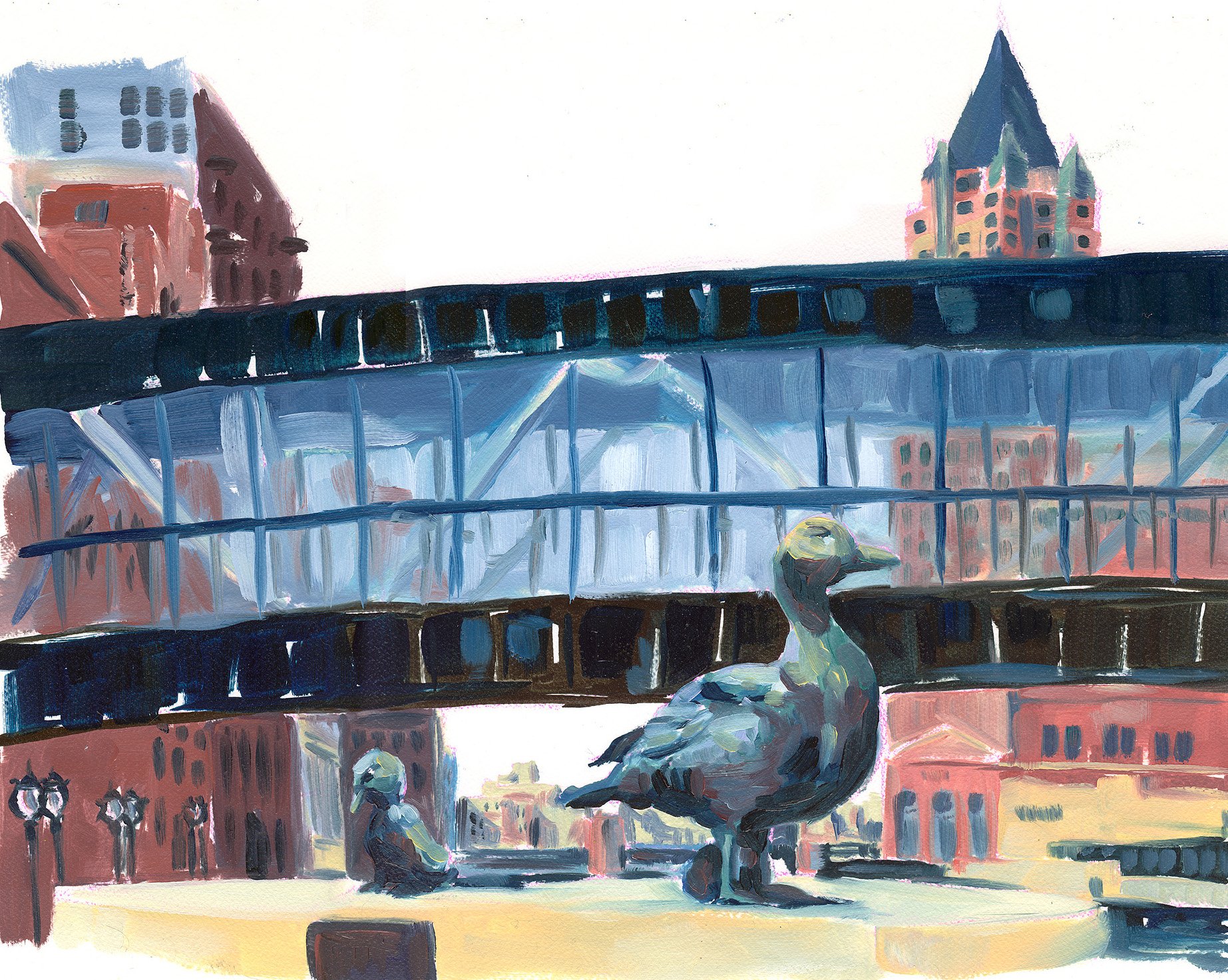

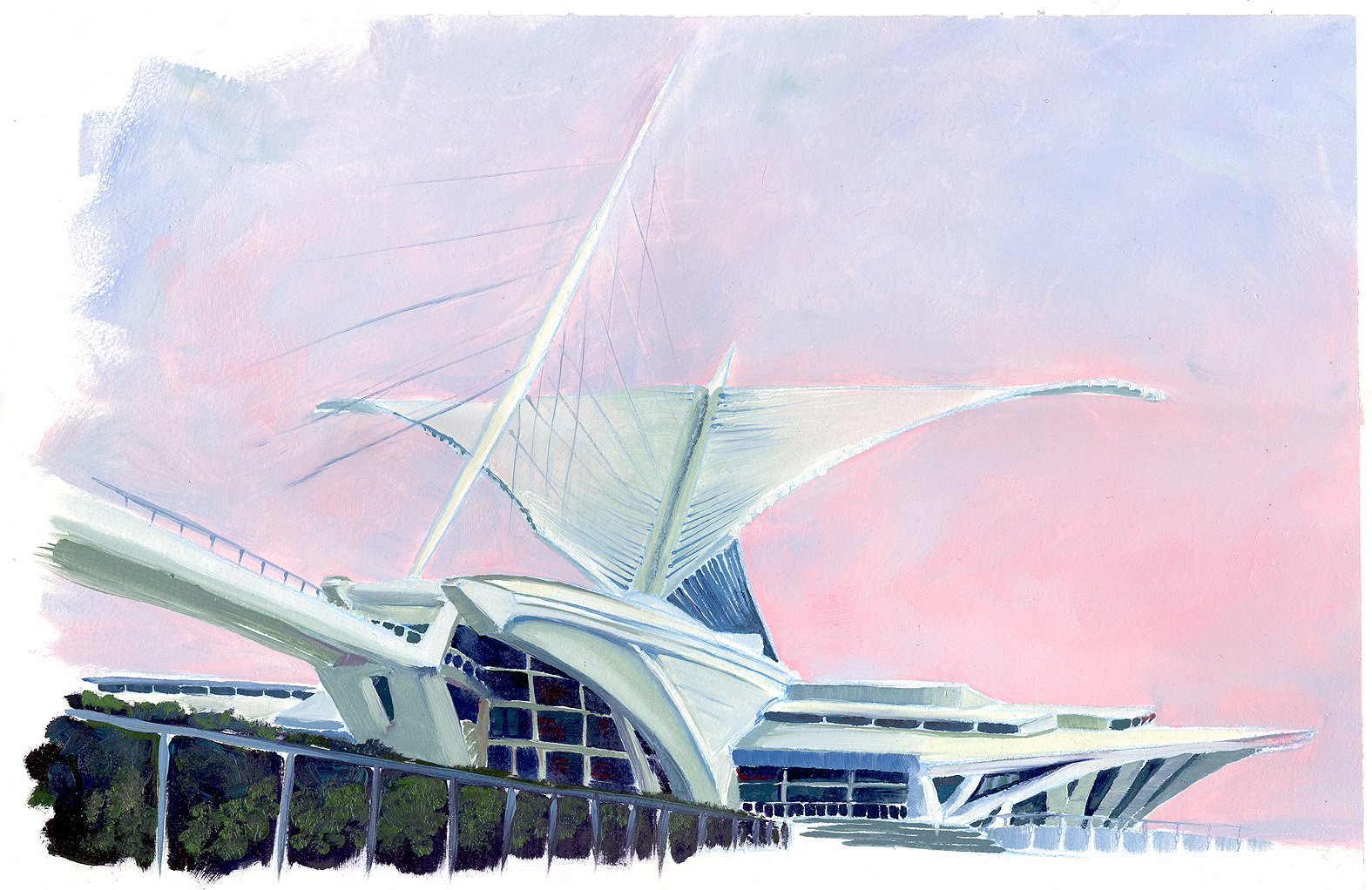

The Milwaukee Sketchbook project was a group of fellow student artists creating sketches and renderings of people and places around the city that are iconic and speak to the very nature of this town. I loved this project because I’ve always loved the preserved architectural moments around this city. I visited all my favorite places in every type of weather. Even if that meant a pink sunrise wake-up call by the lakefront in my pj’s, or a rainy night walk to the WI Gas building to see the Art Deco flame reflected in the mirrored street.

My love of buildings came naturally from my dad. He was a master builder and contractor by family trade. He built many houses we lived in and I inherited his plan drawings of our remodeled farmhouse in Niagara, Wisconsin—a home that belonged to my mom and her family.

Historical architectural styles feed my love of place, especially as it defines the background of stories, giving visual cues of time and context. Milwaukee is a treasure trove of history written in its finely preserved buildings styles—Gothic, Victorian, Art Deco, Bauhaus, as well as the more contemporary moving architecture of Calatrava’s skylight at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

You can see the history of wealth in the varied styles of mansions at the top of Lafayette Hill—best observed from the bottom of the hill, winding up the bluff.

While the history of Milwaukee’s diverse craftsmen is on display in public areas, such as the stonemasons who created many business buildings on Wisconsin Avenue, in ornate bank columns, doorways, and pediments. Wood craftsmanship is also on display, preserved Victorian corbels, while their whimsey is displayed in some of the uniquely crafted houses like the Octagon house and the Boathouse.

Everywhere architectural moment I visited produced 2x3 inch tight thumbnails and was often recreated, in an overpainted xerox or a 3x4 foot oil sketch on gessoed watercolor paper. Thirteen of my sketches and paintings were published in the book, and my painting of the Milwaukee Gas Light Building in the rain was featured in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel to announce the book launch. Eleven of my sketches were bought into the corporate collection of the Northwestern Insurance Company.

Fine Art

Every artistic discipline requires a story. The medium of delivery and the way in which an artist tells the stories is the only thing that changes. I found changing my delivery from illustration and game-making to Fine Art meant learning a new language. While I was researching how to tell a story with the language of contemporary fine art, I felt drawn to the less contemporary mediums. I did not seek out trendier digital mediums, which were more in line with my professional career.

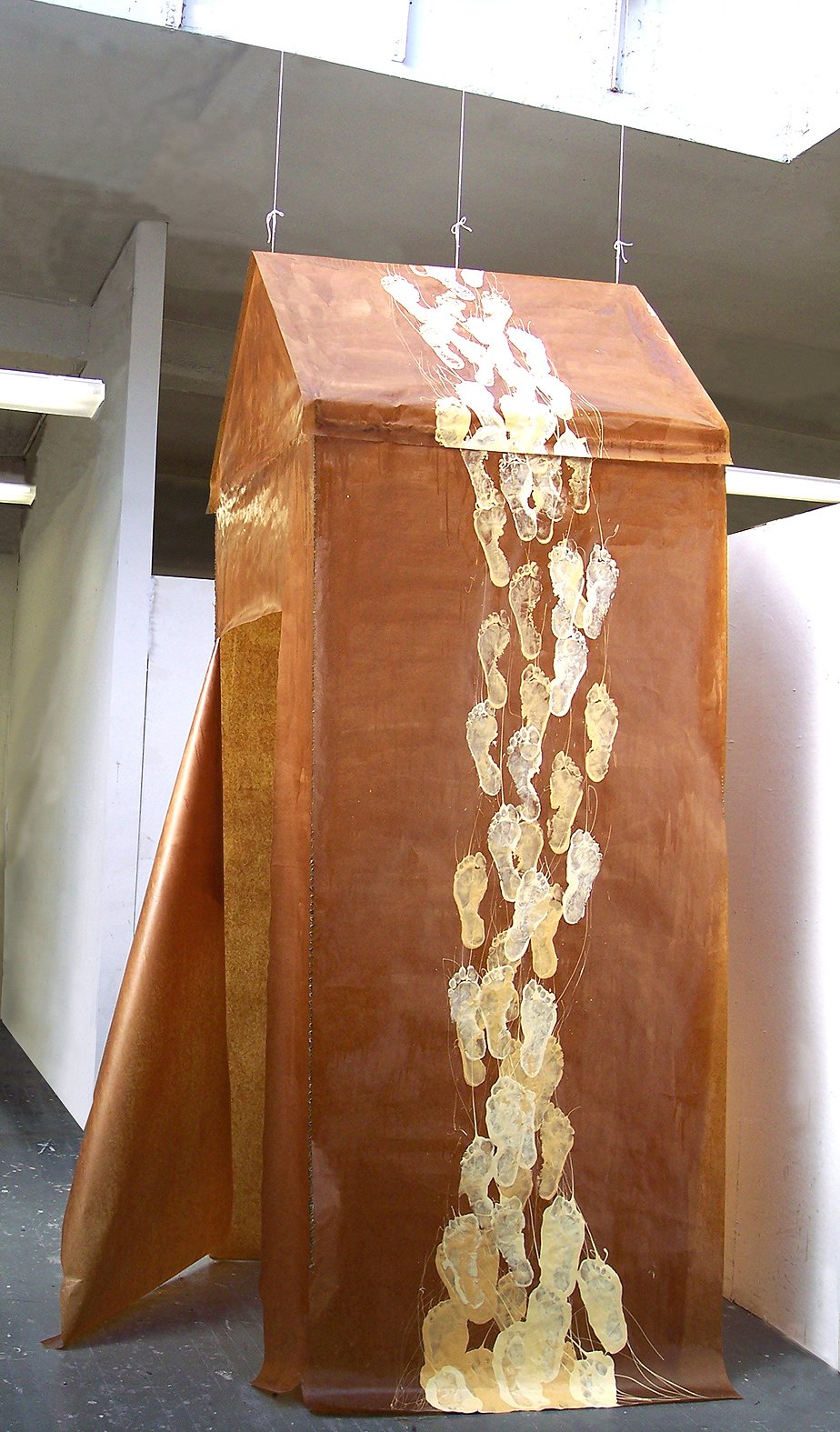

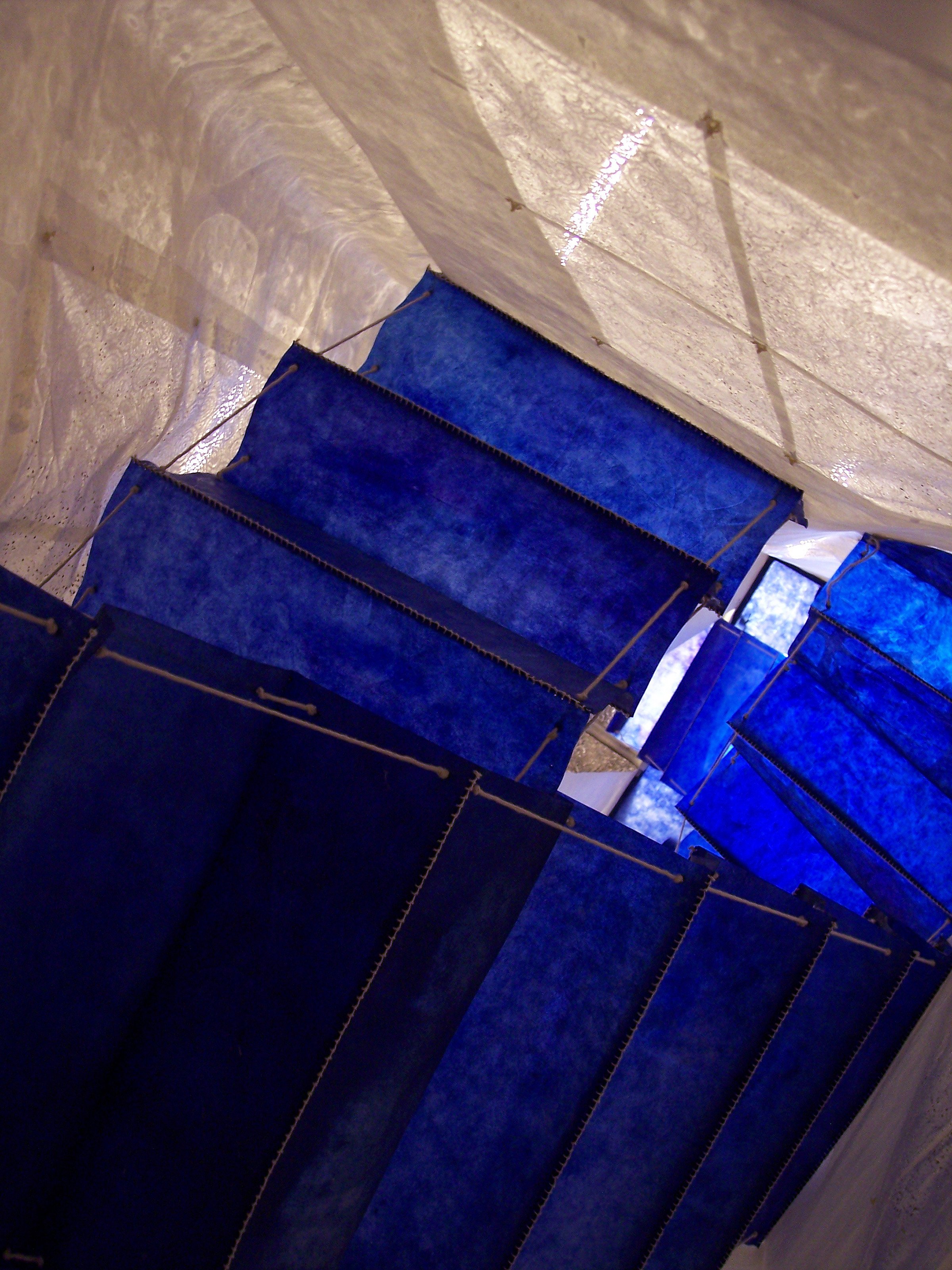

I was instead curious about the ephemeral nature of mediums and created with humble materials such as paper, string, wood, clay, and blades of grass. Perhaps it was a turning back of my youth, where art materials were not available at a local art store, but it’s more likely they were within my budget (after all, blades of grass are quite free). My choice was deliberate, how would non-archivable materials add to the story about my family when juxtaposed against a universally engrained visual symbol of a house.

I was inspired by the magnificent installations of artist Do-Ho Suh, whose highly detailed, diaphanous, fabric recreations of his own homes. I, however, wanted to strip away all the details because a house only becomes a home by what a viewer brings to the symbol. There is no universal meaning for home—it is highly individual. The houses in my “Home” series tell a specific story from my life, but the story it evokes in the view is more important. I invite interaction with open doors that reveals an inner view of the hanging houses, or they tower over the smaller models as they crumble and collapse over time under their own weight.

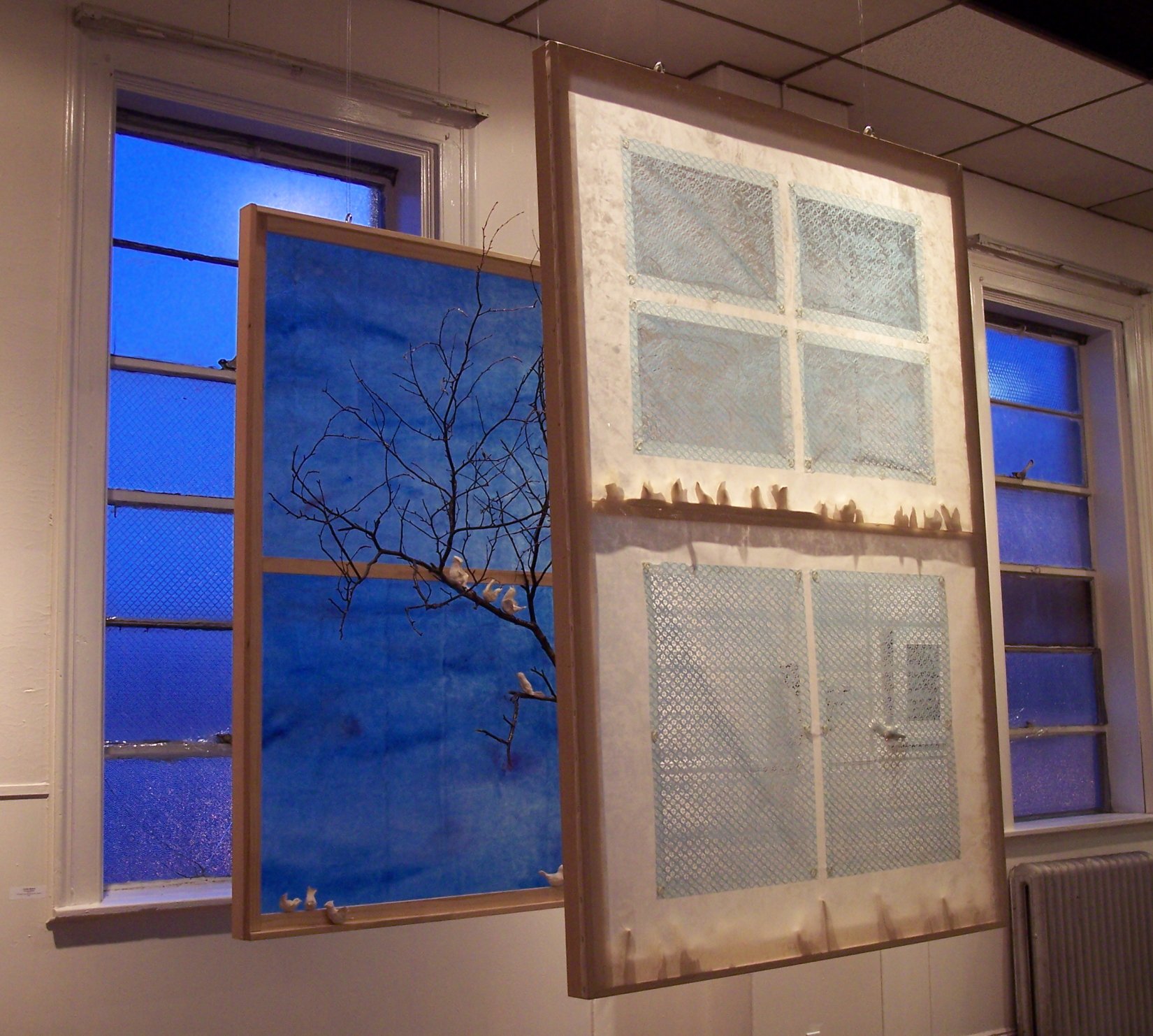

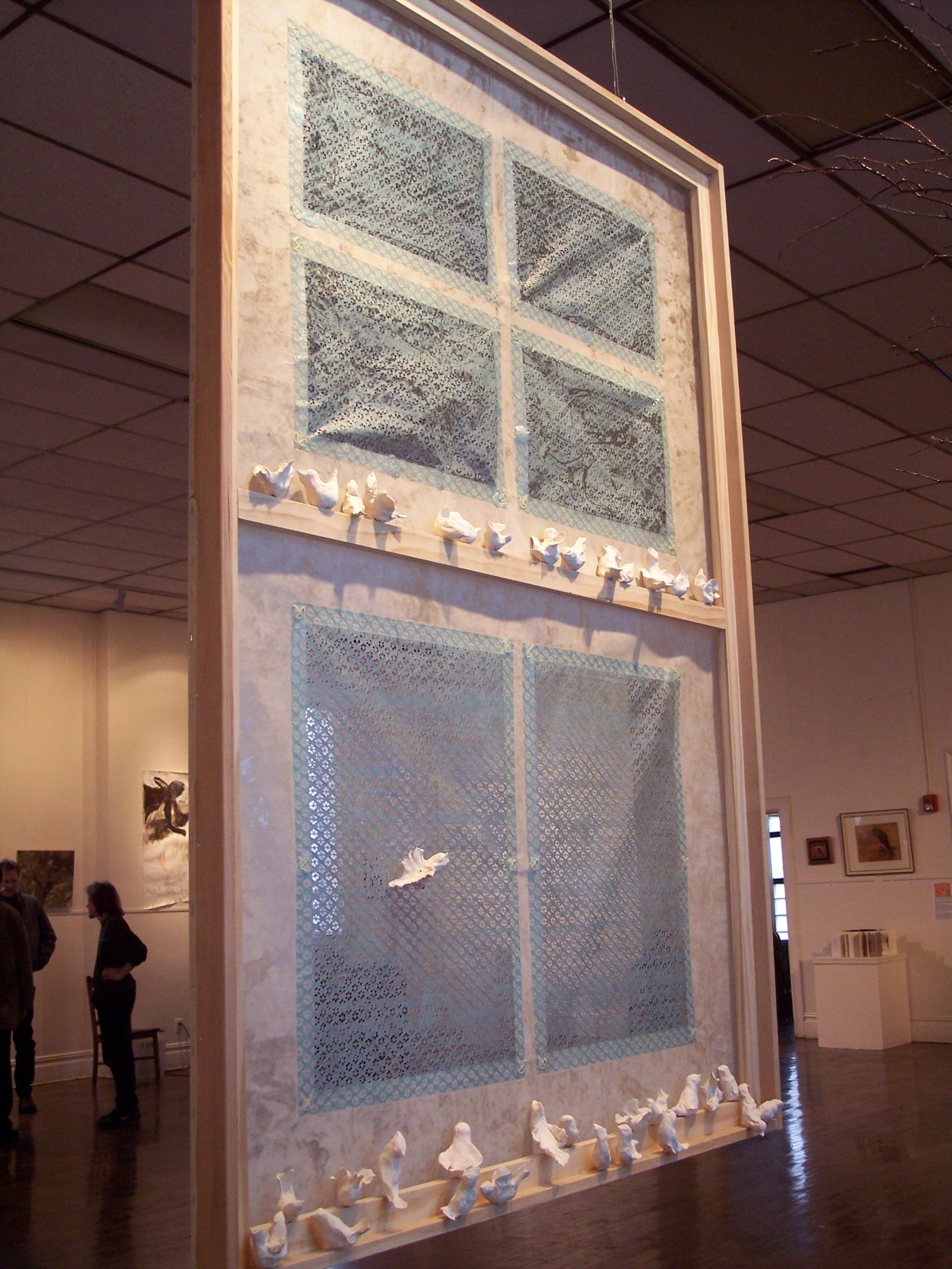

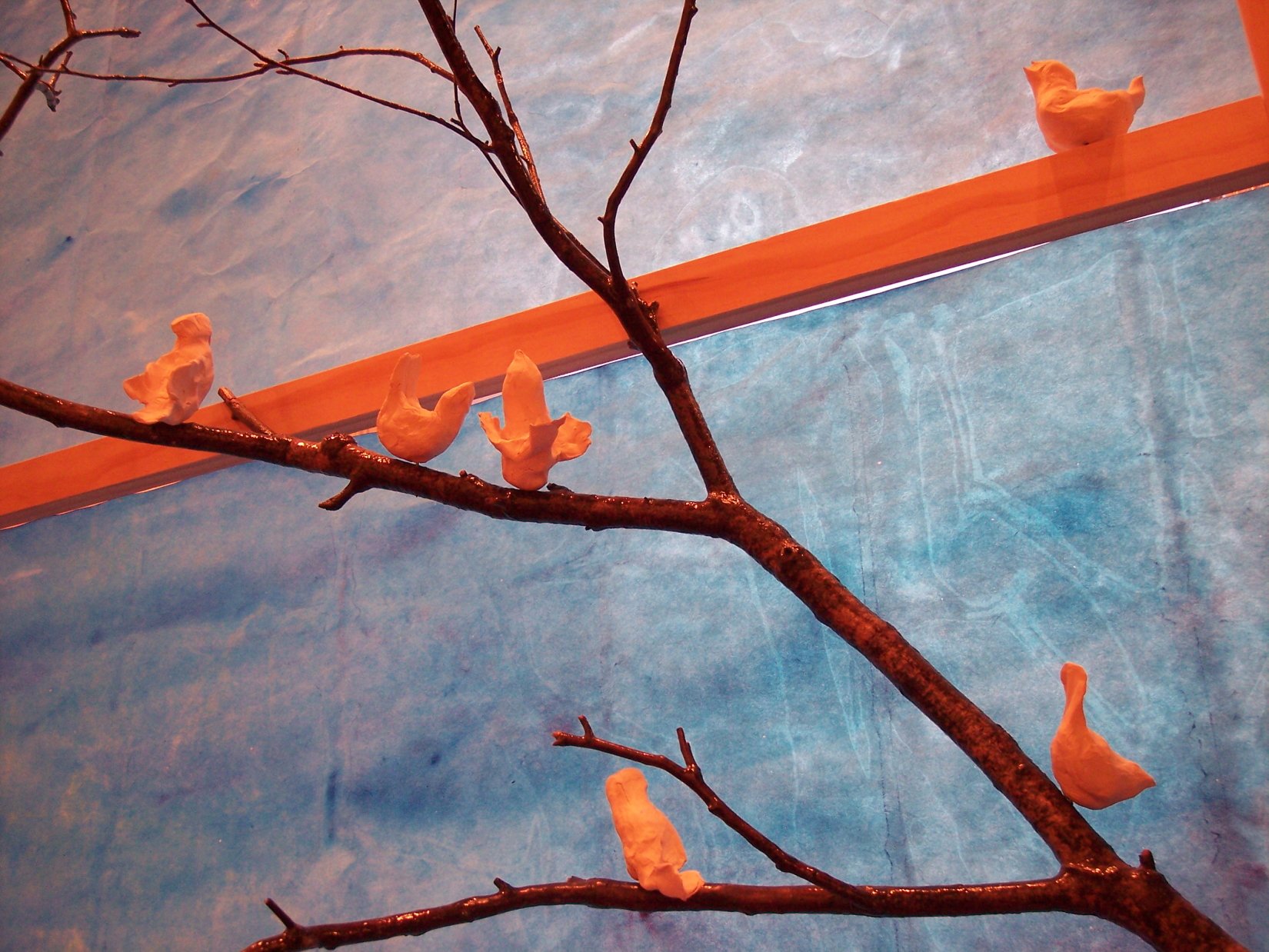

I also invited interaction in my piece, The View Inside, when combined with real windows in the Gallery created a Mobius strip in space—being both inside and outside at the same time. Quickly modeled impressions of birds in bisque fired clay and branches felled from a destroyed mulberry tree outside my apartment, paid homage to the habitat and the fragile bird population that depended on it to thrive. Standing between the false windows during sunset, thanks to the natural light of the west window, cast an ethereal natural glow inside the fabricated place.

The Inside View was one of the dozens of pieces that used the dozens and dozens of bird impressions. As a nod to a dear aunt who taught me to bird-watch, I created small and large installations. Ultimately most birds were given away to the public, outside of a medical center when hung unprotected in the trees that shaded a walkway into a Medical Center.

That gorilla art installation, as well as the wooden wreath of Cedar Wax Wings sharing berries, was titled Altruism. The “Scrubs” piece, seems out of character with the rest but is a portrait of my Mom, a coronary intensive care nurse. I marveled at the way the varnished rice paper looked like skin. I filled the pockets with objects my mom carried in her pockets every day and ultimately brought them home and kept them in a small basket in her closet.

I exhibited my work in several places on the east coast including the Ben Shahn Gallery of Wm Paterson University, NJ, Victory Hall, Jersey City, NJ, and Heidi Cho Gallery in Chelsea, Manhattan, NY, to name a few.